When London hosted the Olympic games in 2012, the number of people using the tube and busses increased dramatically. To help visitors and residents navigate the city’s transport network in these unusual times, Transport for London (TfL) had recruited around 3000 ‘Travel Ambassadors’ from their office staff. These volunteers were trained and licensed to help and complement full-time operational staff in Underground stations, at bus stations, and other hot spots during the event.

This is a concept which we call ‘operational flexibility’ – using trained and briefed staff in a different capacity when required during a crisis, emergency, or other disruptive events.

Other examples of this concept could be using marketing, finance, or project-management staff to answer phones when a crisis causes increased inbound call volumes or using waiters to deliver food locally when the restaurant can’t cater to patrons on-site.

Sounds great, but would that work for you?

There are three things to consider: What would the situations be where you need additional staff? Do these situations lend themselves to operational flexibility? How would you operationalise this?

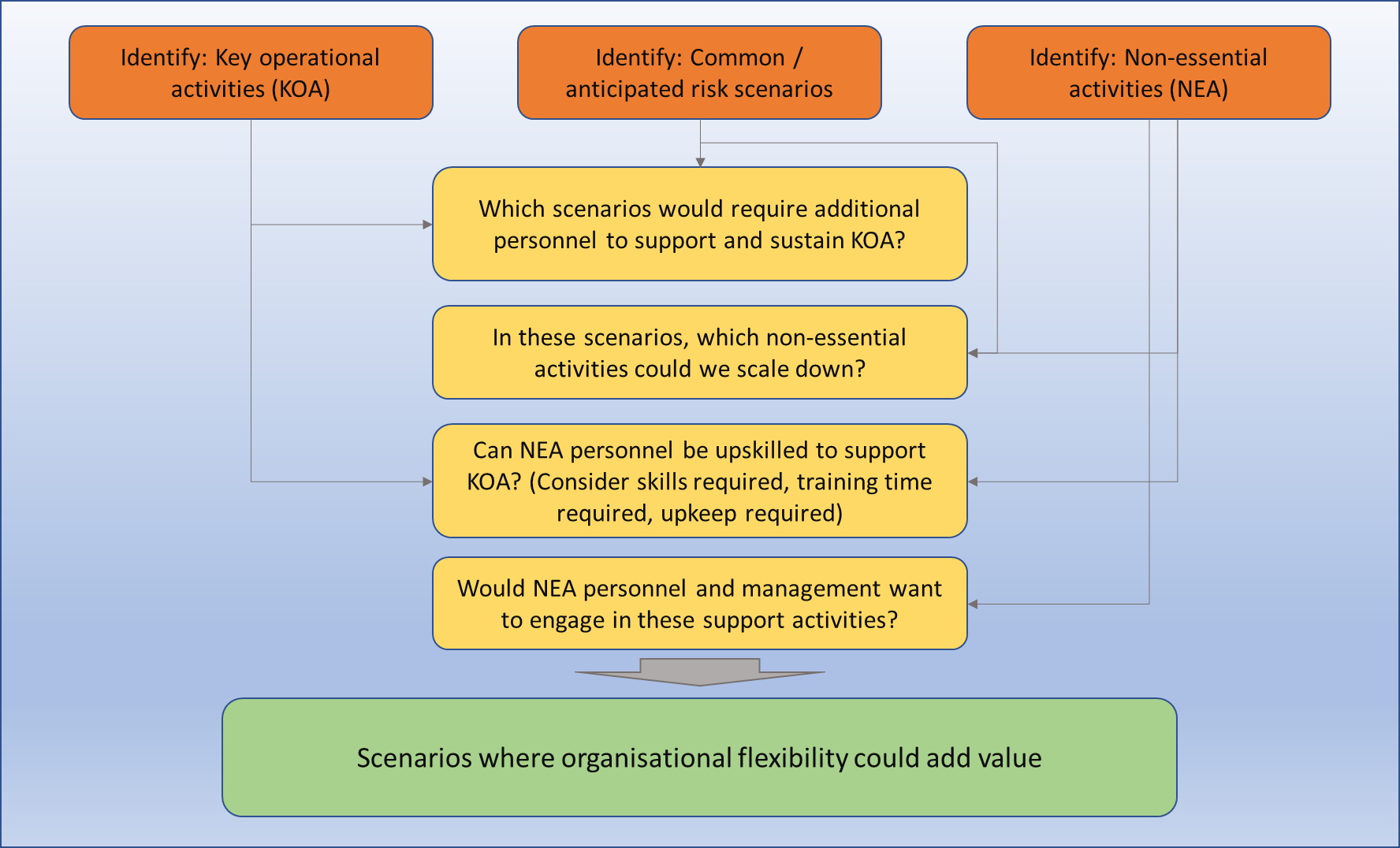

Identify key operational activities (KOA)

The goal is to find out which activities your company or organisation must maintain (at some level) during a crisis. This could be ‘keep trains running’ for a railway company, ‘keep serving food’ for a restaurant, or ‘keep putting out fires’ for a fire brigade. You will also need to consider how long these services could be disrupted to what degree without causing a crisis for your company. (You may also have to think about what a ‘crisis’ would be for your organisation) This is usually done through a business impact analysis and considers the financial impact of different products or services being unavailable for a given amount of time.

Take the restaurant example: Maybe having two or three days with only 75% of covers available is fine, but if this were to drop below 25% for more than a day, your business would take over two months to recover – which in this example is your threshold for a crisis.

Identify common risk scenarios

Once you understand what your KOA are, you can look at scenarios that would disrupt them. Try thinking high-level first, and then break it down. For example, you could consider

- Unavailability of (key) staff

- Demand for products or services dropping suddenly

- Unavailability of supplies or partners you rely on

- Technical disruptions (IT, power,…)

Identify non-essential activities

In this step, look at your KOA and risk scenarios and think about all the other things you do. What could you do without (or do at a reduced level) during a crisis? Could you pause project work for a day or a week? Could you spare your marketing or finance team for some time?

Once you understand these three factors, you can bring them together and start looking at the scenarios. Think about: Where would additional personnel be useful? Could the available, non-essential personnel be trained to take on some of this work? Would they want to? Could you move essential personnel away from some (easier) tasks and have others take them over?

Not every activity is a good candidate – the more high-skilled they are, the less likely are they going to benefit from organisational flexibility. Our experience shows that customer service roles are usually a good fit, but we’ve also seen this concept used to have office staff do hands-on work on a factory floor.

Of course, buy-in is essential – conducting this whole exercise with stakeholders from all parts of your organisation can make it much more transparent and inclusive. You may find that staff would enjoy learning about and getting involved in other parts of your company!

Taking things forward

Once you have your scenarios, you need to

- Talk to employees, explain what’s going on, and motivate them for the programme. You should consider whether a mandatory or volunteer programme would be a better fit for your organisation.

- Develop a training plan. Skills do need to be kept up to date, and the plan should allow for continuous training.

- Develop communications and operational plans. Think about how reporting lines would change in a crisis.

- Test and review. If you activate this system for the first time when disaster strikes, it is likely to fail. You will need to test and train this at least twice a year so that things will go smoothly when required. Always conduct after-action reviews after training and actual incidents.